Distal humeral surgical and developmental anatomy

1. Introduction

An understanding of the anatomy, biomechanics and growth plate patterns of the distal humerus is vital to the rational consideration of fracture care in children.

2. Morphology

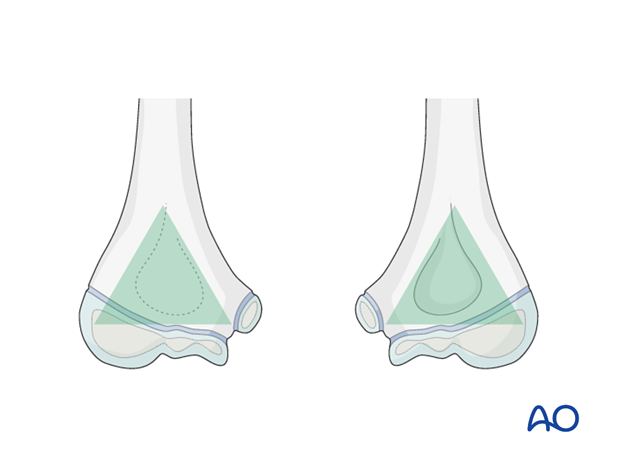

In the child, the distal humerus is an osteochondral block, of roughly triangular shape, attached to the distal humeral diaphysis.

The base of the triangle comprises the transverse condylar mass. This mass is composed of the lateral epicondyle, the capitellum, the trochlea and the medial epicondyle.

The condylar mass is attached to the distal shaft by two supracondylar pillars of bone, one medial and one lateral, forming the other two sides of the triangle.

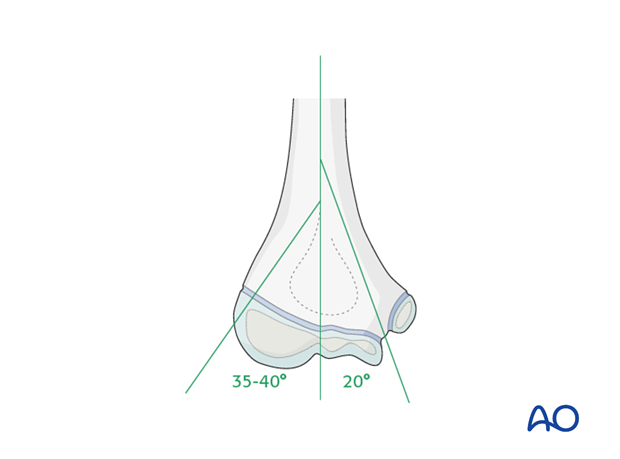

The medial supracondylar pillar subtends an angle of approximately 20° with the long axis of the shaft, and the lateral pillar subtends an angle of about 35-40° with the shaft axis.

The condylar mass is angled anteriorly so that, on the lateral side, the center of the capitellar sphere is level with the front of the humeral shaft. The lateral pillar is consequently curved forwards.

In contrast, on the medial side, the pillar is aligned with the central longitudinal axis of the shaft.

The bone between the two pillars, immediately proximal to the condylar mass, is the site of the olecranon and coronoid fossae and is thin or even absent.

The cross-section of the bone at this level is dumbbell shaped.

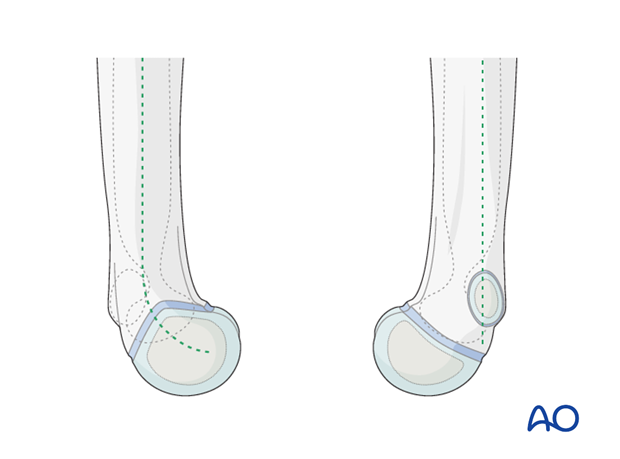

The intramedullary track of the medial column is narrower than that of the lateral column. The degree of discrepancy varies from individual to individual and with age.

3. Articulations

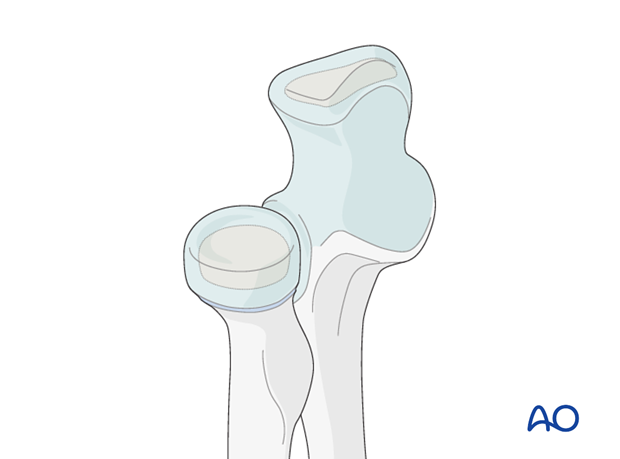

The articular cartilage of the trochlea (medial condyle) covers 270° of its circumference, whereas the posterior half of the lateral condyle is non-articular and is, therefore, available for the attachment, or insertion, of implants.

The trochlea of the distal humerus articulates with the trochlear notch of the olecranon, and the capitellum articulates with the radial head. The superior radioulnar joint completes the elbow joint complex.

4. Developmental anatomy

It is important to understand that the great majority of the longitudinal growth of the humerus takes place at the proximal growth zones at the shoulder.

The implication of this is that any physeal compromise of the distal humerus will have less effect than at for example the distal femur or ankle.

The downside of this observation is that the capacity for modelling malunion is minimal.

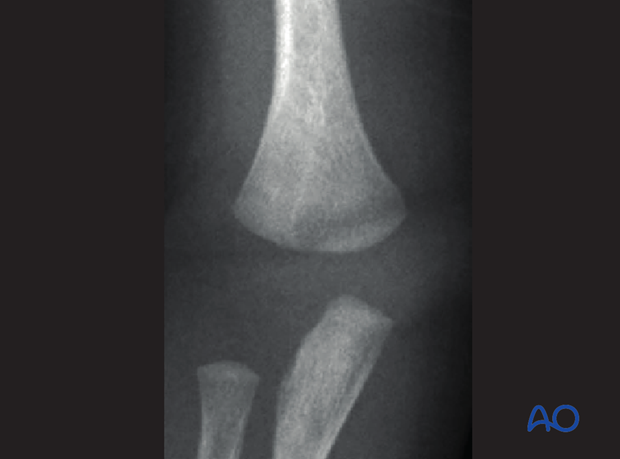

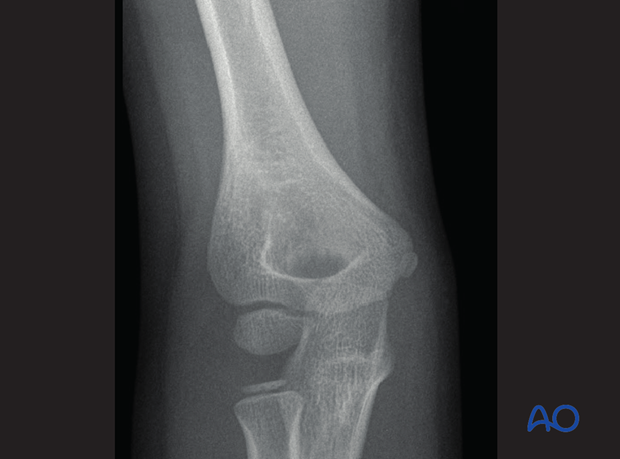

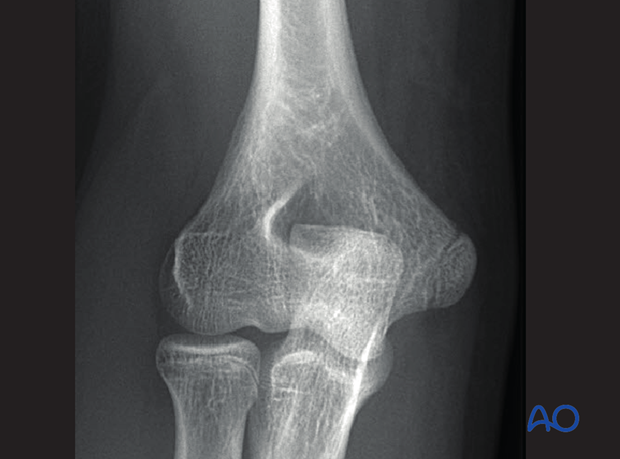

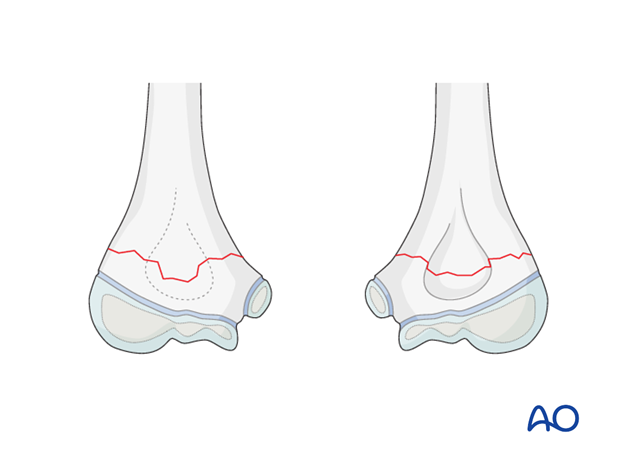

At birth, the whole distal humeral epiphysis is cartilaginous, being the anlage of the capitellum, the trochlea and the two epicondyles. The physis is approximately horizontal.

Radiologically, only the metaphysis/diaphysis is seen.

The capitellar ossific center appears between 9 and 12 months.

The medial epicondylar ossific center starts to appear at about 5-6 years.

The capitellar ossific center progressively enlarges and then, at about 10 to 11 years, the ossific center of the trochlea appears.

The center for the lateral epicondyle also appears around this age.

The capitellar and trochlear ossific centers start to coalesce at about 11-12 years.

The lateral epicondylar ossific center and that of the capitello-trochlear fuse together at around 12-13 years.

By 14-16 years the physis is closed, with the exception of the medial apophysis, which is last to fuse.

5. Fracture pathoanatomy

The thinning of the bone, due to the presence of the fossae between the supracondylar pillars, can act as a stress riser and result in fracture of the bone in the supracondylar region under excessive mechanical load.

The tendency to hyperextension of the child's elbow also contributes to the concentration of stress at this point and the high incidence of extension type supracondylar fractures.

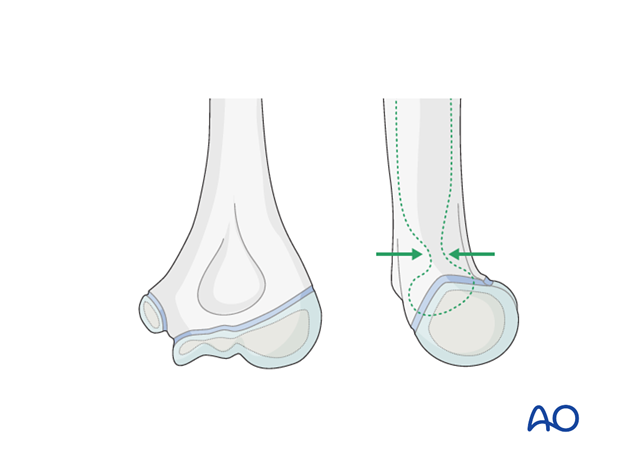

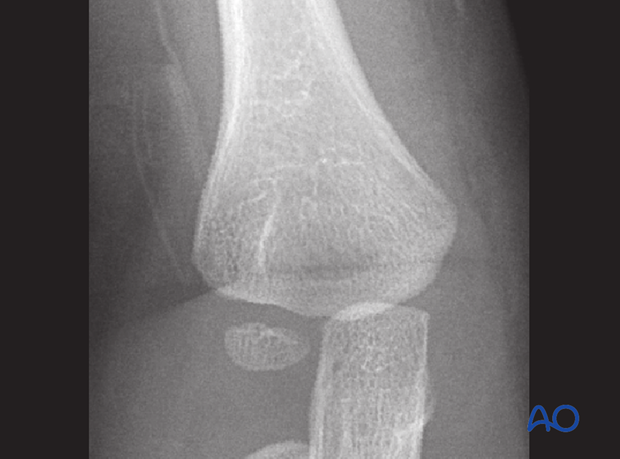

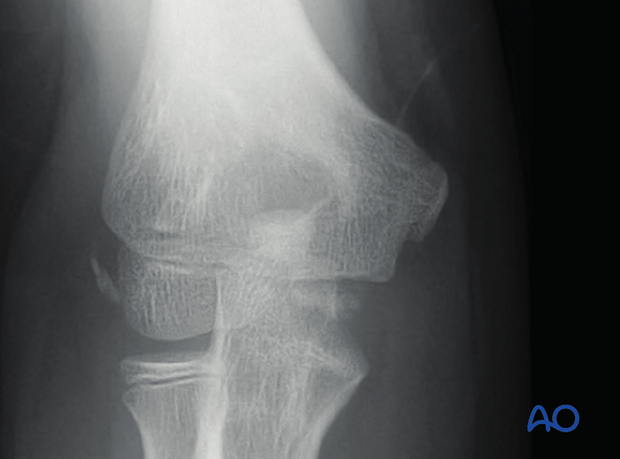

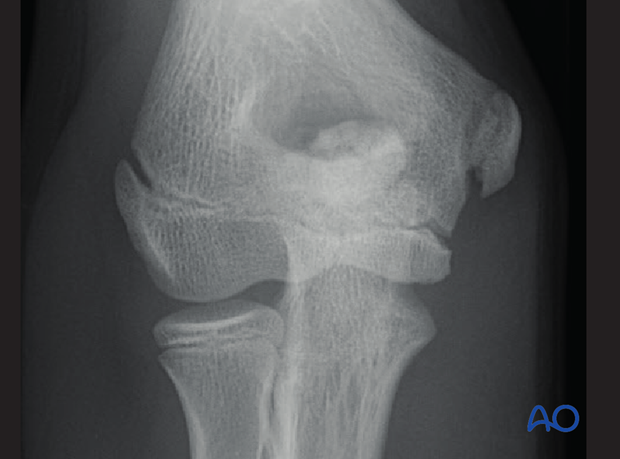

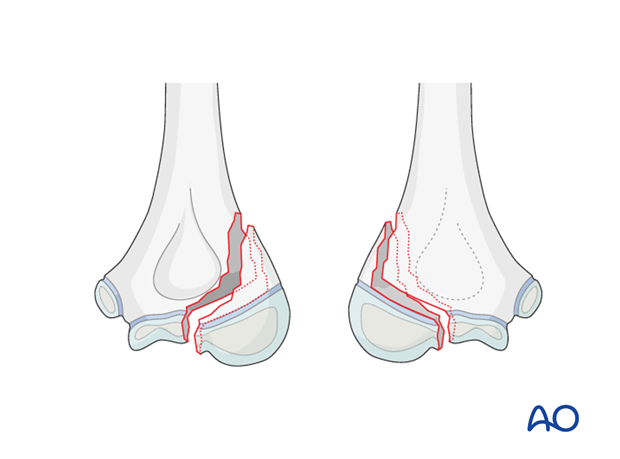

The posterior aspect of the distal portion of the lateral supracondylar ridge is strong and bulky. When an excessive axial compressive force is transmitted through the lateral condyle, often due to a high-energy valgus deformation of the elbow, with a rotational component, a fracture line can separate the capitellum from the trochlea and the posterolateral portion of the lateral pillar breaks off with it, as a Salter-Harris type IV (variant) injury.

It is important to note that the metaphyseal portion of the fragment is more posterior than lateral. This determines the approach for surgical fixation of these injuries.

Note: This is a "triplane fracture" of the distal humerus.

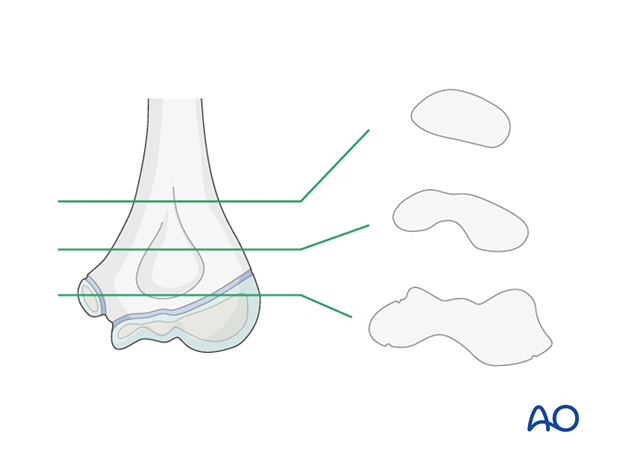

It can be seen that this cleavage has three planes:

- A vertical sagittal split in the epiphysis

- A horizontal shear portion of the physis

- An oblique vertical fracture of the posterolateral portion of the metaphysis, almost in the coronal plane

Thinking of it as a triplane fracture aids the understanding of the anatomy and decision making in relation to implant placement.

6. Vascular anatomy

In Salter-Harris IV injuries, the remaining vascular supply to the metaphyseal-epiphyseal posterolateral fragment derives from the soft tissue attachments to the metaphyseal fragment. Any surgical approach should therefore be as direct and atraumatic as possible, without unnecessary soft tissue stripping, and particular respect for the perichondrial vascular ring.

The standard Kocher lateral approach is, in consequence, not appropriate for lateral condylar triplane injuries.

See:

- Mohan N, Hunter JB, Colton CL. The posterolateral approach to the distal humerus for open reduction and internal fixation of fractures of the lateral condyle in children. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000 Jul;82(5):643-645.