Fractures in abnormal bone

1. Introduction

Fractures may occur more easily in bone which is weakened or more brittle, either locally, or generally.

The nature of the abnormality of the bone may have an impact on surgical techniques that may be needed to stabilize the fracture.

Localized abnormalities include:

Benign conditions

- Unicameral bone cysts

- Fibrous dysplasia

- Osteomyelitis

Malignant conditions

- Sarcomata

- Metastatic tumors

Mechanical conditions

- Preexisting deformity

- Previous fracture or surgical intervention (see section on fractures around implants)

Generalized abnormalities include:

Congenital

- Congenital tibial bowing

- Mucpolysaccharidoses

- Neurofibromatosis

- Osteogenesis imperfecta

- Osteopetrosis

- Skeletal dysplasias

Acquired

- Osteomalacia

- Osteoporosis

- Paraplegia and other motor neurological conditions

- Rickets

2. Localized benign lesions

Unicameral bone cyst

Unfractured lesions are commonest in the proximal humerus, the proximal femur and the calcaneum.

They are usually treated by ablative injection techniques. [1, 2]

If fracture occurs, conservative measures will usually result in fracture healing – if the cyst persists, then injection therapy is indicated.

All such cysts fill in by skeletal maturity.

Flexible intramedullary nails may be required if surgical stabilization is required. [3]

Monostotic fibrous dysplasia

Fibrous dysplasia (FD) is a disorder involving either one (monostotic) or several bones (polyostotic FD) and sometimes is associated with cafė-au-lait hyperpigmentation of the skin and one or more hyperfunctioning endocrinopathies (McCune-Albright syndrome [MAS]).

Both PFD and MAS are often associated with phosphaturia. Although fractures occur frequently in PFD/MAS, fracture incidence and the effect of age and co-existing metabolic abnormalities (endocrinopathy and/or phosphaturia) on fractures are ill-defined. [4]

The classical ground glass appearance of the lesion aids diagnosis. [5]

Such fractures are usually precipitated by a degree of violence, such as a fall, rather than being spontaneous.

They are likely to heal with nonoperative management, but intramedullary fixation may be indicated to control deformity. [6]

In patients with polyostotic fibrous dysplasia of bone, the peak incidence of fractures is during the first decade of life, followed by a decrease thereafter. Phosphaturia is associated with an earlier incidence and increased frequency of fractures.

Surgical treatment of preference is intramedullary nailing.

Osteomyelitis

Fractures through bone affected by osteomyelitis are rare.

Osteosynthesis is precluded in the presence of continuing infection.

The treatment is predicated on eradicating the infection by surgical and pharmacological interventions.

Pseudarthrosis may result: this is treated by standard methods once infection can be excluded.

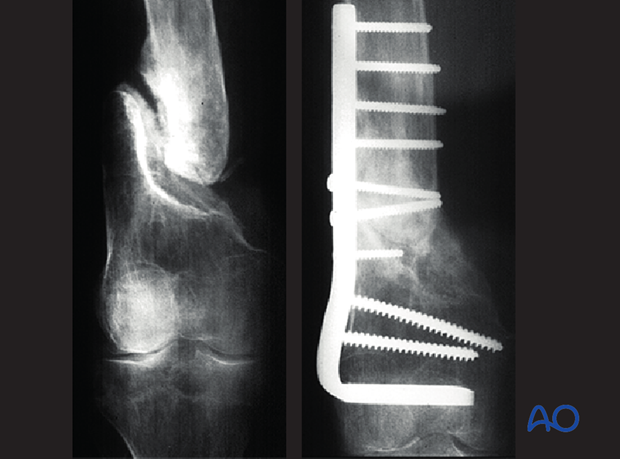

Illustrative case:

Nonunion 38 years after fracture through osteomyelitis as a teenager. United rapidly with Judet decortication, rigid fixation and autogenous bone-grafting.

3. Localized malignant conditions

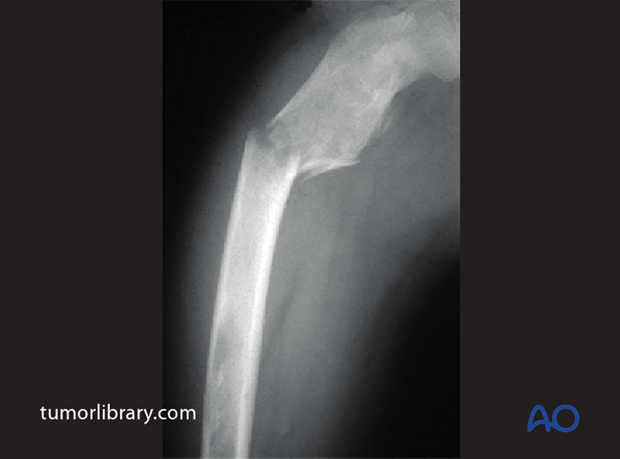

Sarcomata

The treatment of pathological fractures through bone sarcomata is predicated on the management of the malignant lesion. Fracture is likely to favor amputation rather than conservative surgery, but this care should be conducted in specialized bone tumor centers. Modern advances in conservative, prosthetic surgery, combined with advanced chemotherapeutic techniques are resulting in a constantly changing picture. [7, 8]

Case courtesy of A.Prof Frank Gaillard, Radiopaedia.org, from the case rID: 7530

Metastatic tumors

The management of pathological fractures through metastatic tumors is determined by the nature of the primary neoplasm, the patient’s general prognosis and any prospects for chemo- and radio-therapeutic intervention.

Surgical stabilization is highly desirable in the interests of the patient’s comfort and care. This may be combined with local radiotherapy and/or systemic chemotherapeutic agents.

The surgical technique must be chosen to take into account the location of the lesion and the state of the remainder of the affected bone. Intramedullary nailing is often the optimal method for diaphyseal fractures of this type.

4. Localized mechanical conditions

Pre-existing deformity

Localized bony deformity can result in abnormal stresses on the bone and secondary fracture – either stress fracture or acute fracture.

Such deformities may be isolated developmental abnormalities or due to previous abnormalities of union.

The fracture affords the opportunity to correct the deformity whilst stabilizing the fracture.

The nature of the fixation method will be determined by the pathology, the nature of the deformity, skeletal maturity, and the status of the adjacent bone

Case illustrated - tenuous union in late adolescence, following a high-energy fracture towards skeletal maturity, with marked deformity, resulted in further fracture and increase in the deformity.

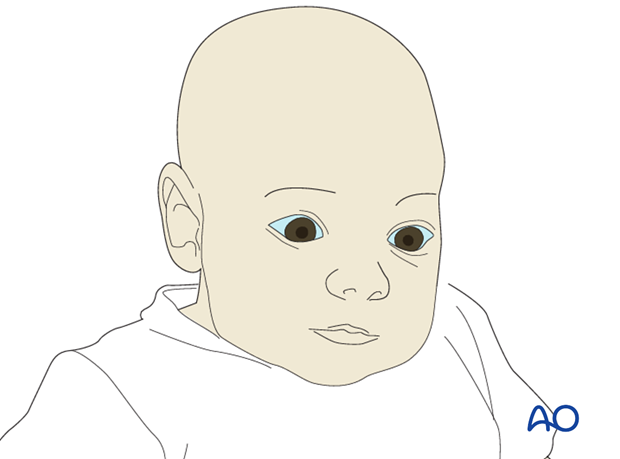

Osteogenesis imperfect (OI)

Various degrees of expression of this congenital brittle bone disease are seen – types I-IV.

Type I:

- Is the mildest and most common form of the disorder. It accounts for 50 percent of the total OI population

- Is characterized by mild bone fragility, relatively few fractures, and minimal limb deformities. The child might not fracture until he or she is learning to walk

- Shoulder and elbow dislocations may occur more frequently than in healthy children

- Some children have few obvious signs of OI or fractures. Others experience multiple fractures of the long bones, compression fractures of the vertebrae, and chronic pain

- The intervals between fractures may vary considerably

- Blue sclera are often present

- After growth is completed, the incidence of fractures decreases considerably

Type II:

- Is the most severe form

- At birth, infants with OI type II have very short limbs, small chests, and soft skulls. Their legs are often in a frog-leg position

- Intrauterine fractures will be evident in the skull, long bones, and/or vertebrae

- The sclera are usually very dark blue or gray

Type III:

- Is the most severe type among those children who survive the neonatal period. The degree of bone fragility and the fracture rate vary widely

- This type is characterized by structurally defective type I collagen

Type IV:

- People with OI Type IV are moderately affected. They may not fracture until after walking

- Typically have light blue sclera

Deformities often result and these often need correction. Telescopic intramedullary nails are often used to stabilize fractures, or multiple level osteotomies, whilst permitting continued longitudinal growth.

See nonaccidental injury section for discussion of osteogenesis imperfecta in relation to nonaccidental injuries.

Reprinted by permission from Macmillan Publishers Ltd: GENE THERAPY ( Niyibizi C, Wang S, Mi Z, et al. Gene therapy approaches for osteogenesis imperfecta. Gene Ther . 2004 Feb;11(4):408-416), copyright (2004)

Other congenital abnormalities

Other congenital abnormalities include:

- Skeletal dysplasias

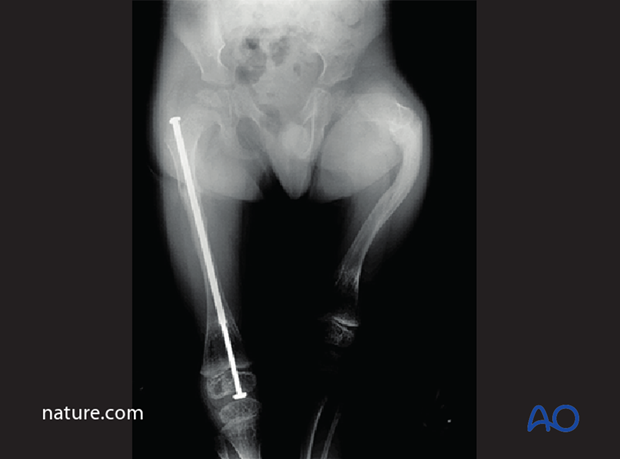

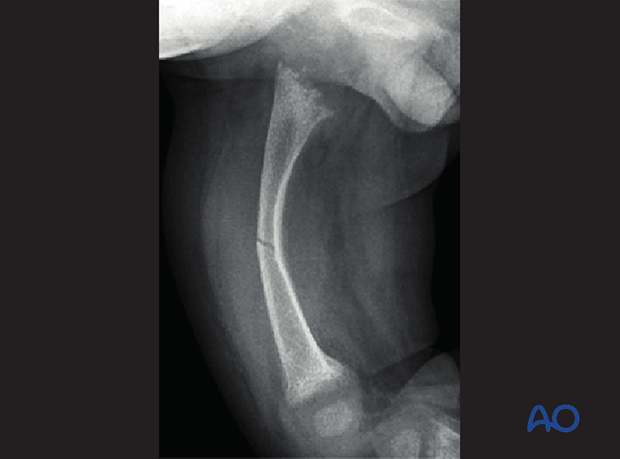

- Congenital tibial bowing (illustrated)

- Mucopolysaccharidoses

- Neurofibromatosis

- Osteopetrosis

- Skeletal dysplasias

In these conditions, it is usually deformity, combined with changes in the mechanical properties of the bone that results in fracture, although in osteopetrosis, the brittleness of the bone is the major cause.

These are rare conditions and should be referred to a specialist unit

Illustrated case - pathological fracture of tibia in a child with neurofibromatosis: this is likely to develop into a pseudarthrosis; management is highly specialized and requires particular experience in the management of this condition.

5. Metabolic bone disease

Rickets

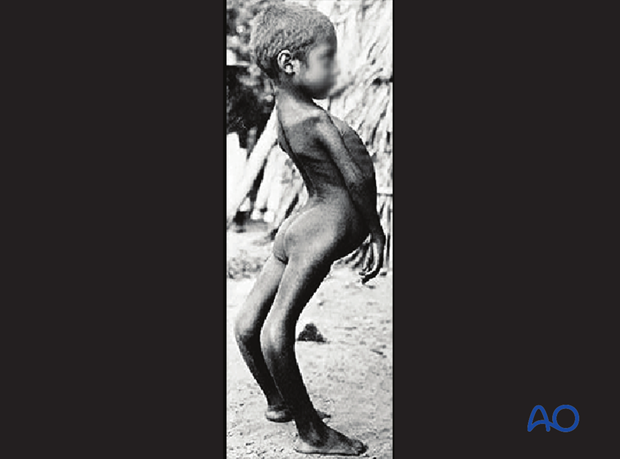

The condition

Rickets, once thought vanquished, is reappearing. In some less-developed countries it hardly went away. Rickets can be secondary to disorders of the gut, pancreas, liver, kidney, or metabolism; however, it is mostly due to nutritional deficiency. Although calcium deficiency contributes in communities where little cows' milk is consumed, deficiency of vitamin D is the main cause.

There are three major problems:

- The promotion of exclusive breastfeeding for long periods without vitamin D supplementation, particularly for babies whose mothers are vitamin D deficient

- Reduced opportunities for production of the vitamin in the skin because of female modesty and fear of skin cancer

- The high prevalence of rickets in immigrant groups in more temperate regions, often associated with foods high in phytic acid

A safety net of extra-dietary vitamin D should be reemphasized, not only for children, but also for pregnant women.

The reason why many immigrant children in temperate zones have vitamin D deficiency is unclear. We speculate that in addition to differences in genetic factors, sun exposure, and skin pigmentation, iron deficiency may affect vitamin D handling in the skin or gut or its intermediary metabolism [9].

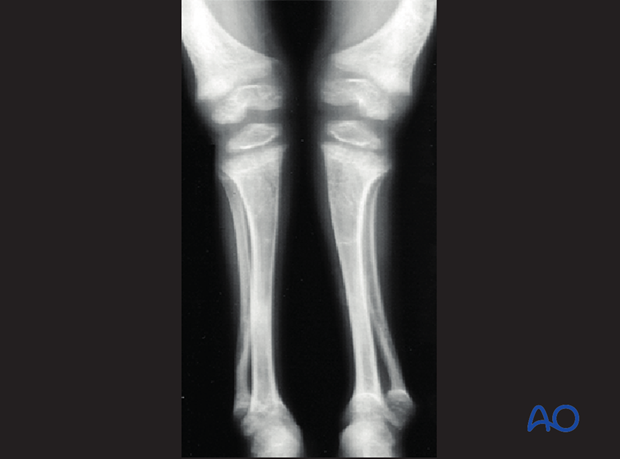

This image shows severe rickets with bony deformities and classical deeply “cupped” physeal/metaphyseal appearances.

Fractures in rickets

Rachitic fractures occur in very-low-birth-weight infants in association with developmental nutritional rickets [10].

Spontaneous fractures in rickets are very rare. They were first reported in 1906 by Henry Feiss [11].

The treatment of fractures in rickets follows protocols for fractures in normal bone, plus any deformity correction and the therapeutic management of the underlying disease.

It must be borne in mind that rachitic bone has reduced screw-holding characteristics, should osteosynthesis be considered.

Paraplegia and other neurological conditions

Paralysis of limbs, over time, results in marked osteopenia and a predisposition to fractures of the affected bones.

The management of such fractures depends on the nature of the neurological deficit, the patient’s general level of pre-fracture handicap, and the status of the affected bone.

Fixation can present severe problems, as in marked osteoporosis.

6. References

[1] Rougraff BT, Kling TJ. Treatment of active unicameral bone cysts with percutaneous injection of demineralized bone matrix and autogenous bone marrow. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002 Jun;84-A(6):921-929.

[2] Chang CH, Stanton RP, Glutting J. Unicameral bone cysts treated by injection of bone marrow or methylprednisolone. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002 Apr;84(3):407-412.

[3] Roposch A, Saraph V, Linhart WE. Flexible intramedullary nailing for the treatment of unicameral bone cysts in long bones. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2000 Oct;82-A(10):1447-1453.

[4] Leet AI, Chebli C, Kushner H, et al. Fracture incidence in polyostotic fibrous dysplasia and the McCune-Albright syndrome. J Bone Miner Res. 2004 Apr;19(4):571-577.

[5] Henry A. Monostotic fibrous dysplasia. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1969 May;51(2):300-306.

[6] Han I, Choi ES, Kim HS. Monostotic fibrous dysplasia of the proximal femur: natural history and predisposing factors for disease progression. Bone Joint J. 2014 May;96-B(5):673-676.

[7] Bacci G, Ferrari S, Longhi A, et al. Nonmetastatic osteosarcoma of the extremity with pathologic fracture at presentation: local and systemic control by amputation or limb salvage after preoperative chemotherapy. Acta Orthop Scand. 2003 Aug;74(4):449-454.

[8] Bramer JA, Abudu AA, Grimer RJ, et al. Do pathological fractures influence survival and local recurrence rate in bony sarcomas? Eur J Cancer. 2007 Sep;43(13):1944-1951.

[9] Wharton B, Bishop N. Rickets. Lancet. 2003 Oct;362(9393):1389-1400.

[10] Dabezies EJ, Warren PD. Fractures in very low birth weight infants with rickets. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1997 Feb;(335):233-239.

[11] Feiss HO. Spontaneous fractures with rickets. Report of a case. Am J Orthop Surg. 1906 Jan;23(3):271-278.).