General considerations with mandible fractures

1. Biomechanics of the mandibles

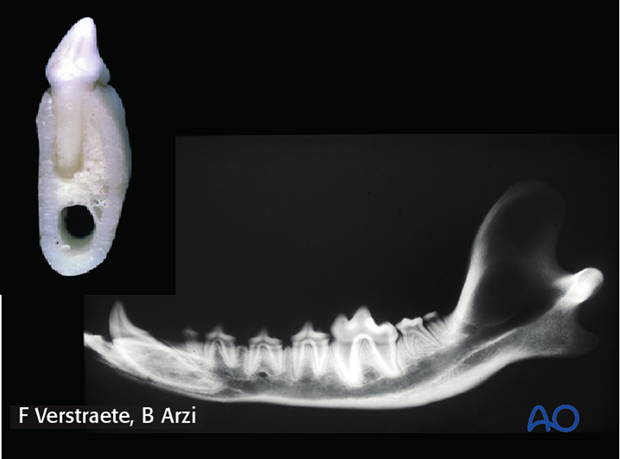

Biomechanically, the mandible is a strong, but lightweight bone. It is connected by a fibrocartilaginous joint rostrally and articulated caudally at the TMJ. The mandible bone has 2 bony parts: the alveolar process (tooth bearing bone) and the basal bone that lies ventral to the alveolar bone and is not tooth bearing bone. A neurovascular bundle (the inferior alveolar blood vessels and nerves) passes at the mid-ventral part of the mandible in the mandibular canal. Therefore, the majority of the mandible is occupied by teeth roots and by the mandibular neurovascular bundle. Treatment plan and fixation methods have to avoid these vital structures.

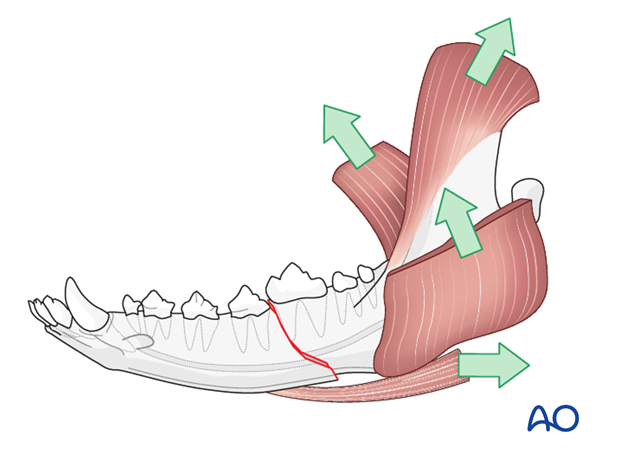

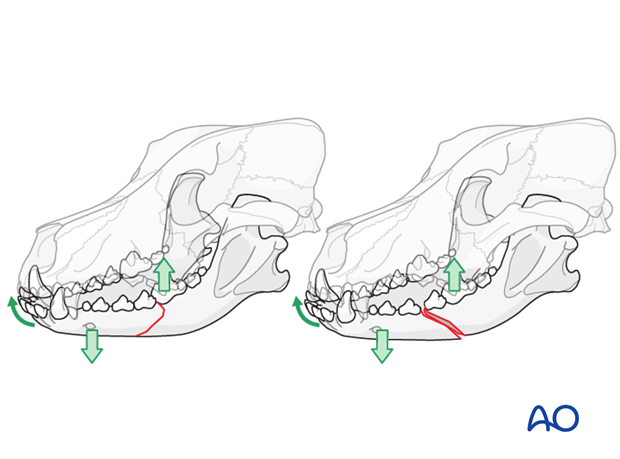

Tensile stresses act on the alveolar margin (the teeth side of the mandible) and the maximum compressive stresses act on the ventral border of the mandible. These dynamics change depending on where the patient chews its food (caudally vs. rostrally).

Fractures of the mandible are classified as ‘favorable’ (relatively stable) when the bone fragments are brought together as the patient closes its mouth. Fractures are classified as ‘unfavorable’ (unstable) when the bone fragments are separated as the patient closes its mouth.

2. Airway considerations

General anesthesia via endotracheal intubation is often used for:

- Imaging

- Surgical procedures that proper occlusion can be judged

- When pharyngostomy feeding tube is placed

Pharyngeal intubation may be needed when dental occlusion is difficult to judge.

Tracheostomy is indicated when the mouth cannot be opened.

3. Surgical principles

The overall goal is to restore occlusion, normal anatomy and function.

In cases where the fracture is displaced or compressed, anatomic reduction and fixation is necessary.

Non-vital bone fragments should be removed and discarded.

The choice of treatment for fracture fixation is determined by:

- Fracture conformation

- Soft tissue trauma

- Viability of the fracture fragments

- Accessibility to the fracture

- Stability after fracture reduction